A New Life in Central New York

Now living in the Oswego County village of Cleveland, actor and producer Daniel Baldwin is helping those with addiction and plans to start a long-term drug recovery facility near Oneida Lake

By Aaron Gifford

Daniel Baldwin had one last shot of beating his old man. It was during his senior year at Alfred G. Berner High School in Long Island. Baldwin was a star football player there and would face cross-town rivals Massapequa, coached by his father, Alexander. Daniel and his brother Alec Baldwin lost to their dad’s team the previous two seasons on varsity. The stakes were high: Losers had to haul the victor in a wheel barrow to the neighborhood Baskin Robbins and pay for ice cream.

On a late fall Saturday afternoon, tired and bruised after a nail biter that came down to a field goal, Alec Baldwin found himself pushing the wheel barrow, his dad gloating all the while.

“Yeah, I lost to my dad all three times. We hauled his butt down the road, and he was heavy,” Daniel Baldwin, 57, growled. “I guess I’d say there was a healthy dose of competition in our house. The bar was pretty high.”

Even though Baldwin enjoys the memory, a slight sense of regret and unsettledness is detected in his voice, as if he still ponders what he and his teammates could have done differently to win the game. That competitive drive helped Baldwin get to where he is today — a movie and television celebrity who still acts and directs — and also a recovering drug addict who has waged a personal war against the opiate epidemic. For both careers, he recently established his base in the Oswego County village of Cleveland, on Oneida Lake. He’s returned to his family’s adopted locale to be closer to his mother Carol, who lives in Camillus, and sisters Beth and Jane, and because the Upstate New York region needs a huge helping hand combating addiction.

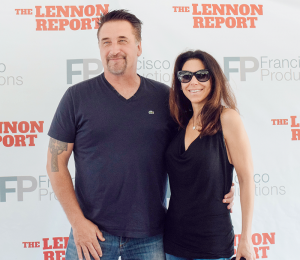

The Central New York experience so far with fiancée Robin Hemple and daughters Avis and Finley, he says, has been magnificent.

“It just seemed like now was the time to move closer to family,” Baldwin said of his mother and sisters. “Being here, I feel like the theme is Green Acres. We just love discovering the area. It’s exciting to get into a car and drive and not even know what we’re going to see.”

Baldwin’s resume includes several big-budget Hollywood pictures, including “Born on the Fourth of July” and “Mullholland Falls,” though he is also quite proud of the independent films he has acted in and directed, including one about drug addiction, “Wisdom to Know the Difference,” which won awards at several film festivals. He says he has six movies coming out in the next 18 months and he also has a role on Hawaii 5-O.

Growing up in a household headed by teachers and coaches, brothers Daniel, Alec, William and Stephen had a difficult time swaying their parents to support their career choice, but all four stuck with it and made it to the big screen.

“Because I was in football, the other players laughed at me for going to drama practice because it wasn’t the macho thing to do,” Baldwin recalled. “But when I was on stage, it was very freeing because it’s just me. As an actor, you can’t be wrong — it’s your interpretation of what’s on the page. I always knew I’d pursue acting.”

As Baldwin sees it, actors get to Hollywood based on looks, talent, timing and luck. Someone can be a bombshell in the looks category or a prodigy in the talent category and get there without much timing or luck. Baldwin thinks he was able to stretch just enough in each of the four categories — 25 percent each — to make it. He got on stage for a few theate productions in New York City, hooked up with an agent and made contacts out west, performing stand-up comedy in Los Angeles to pay the bills while he patiently waited for better opportunities.

Baldwin’s stand-up act was unique: He liked improvisation work, putting audience members as his subjects. He’d ask women to throw something from their purses on stage, then make up a funny story or situation on the spot.

That work opened the door for situation comedies on major networks, and later a main character as Beau Felton on “Homicide: Life on the Street.” Baldwin is proud of his work on that show, but he also felt that to some degree it pigeonholed him into tough guy roles.

“What’s frustrating is producers can get the idea that you can’t be funny, or you can’t be the guy who is gay. Don’t play the same guy for three or four years. You need some diversity, but at the same time you don’t want to walk away from a popular character and the money that goes with it.”

Baldwin faced a similar dilemma on the big screen. With the bigger budget movies, he doesn’t enjoy the repetitiveness of shooting the same scene for weeks on end, but those productions pay well and give you more notoriety. With smaller, independent pictures, he explained, you have more creative freedom and the work is more fun but the payoff is much less.

He has acted in six films that haven’t come out yet, and was to begin work in October for an independent film about FBI profilers that will be filmed right here in Central New York.

As a celebrity, Baldwin became entrenched in the Hollywood lifestyle, working hard, playing hard and experimenting. He got involved heavily in cocaine. It started out as a social drug for Baldwin, but he eventually reached the point where he was smoking it. By the age of 45, he had been in and out of rehab nine times.

Baldwin holds himself responsible for the drug abuse and the lack of success he had getting sober the first eight times. But he also says the environment of blame and guilt that some rehabilitation centers fostered was counterproductive. The last facility he stayed at, SOBA Recovery Center in California, provided a sense of love and healing.

“Getting sober is not the hard part,” Baldwin said, “staying sober is. The problem is when you get out — and so many facilities don’t allow the addicts to stay nearly long enough — you are still in an emotional and psychological jail. All of the trouble and pain, they are still waiting for you as soon as you get out.”

As part of his own sobriety challenge, Baldwin helps other addicts. He will be busy: So far this year, there have been more than 47,000 heroin overdoses nationally in the 15-25 age group, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

“We are on track for 60,000 in 2017,” Baldwin said. “That’s more people than we lost in the Vietnam War.”

Baldwin responds to calls for help via Facebook. In most cases, it’s a parent asking for an intervention. He’s not limited to the local area. On short notice and on his own dime, Baldwin has flown to other states to meet addicts and convince them to go to rehab. He endorses SOBA, which has locations in different states, but tries to offer various options based on the family’s needs and resources. In many cases, SOBA has given client scholarships.

Baldwin is often successful, but not always. The day before he was interviewed for this story, Baldwin found out that a teenager he reached out to died of a fatal heroin overdose. The mother hesitated to put the girl in rehab until after she worked up the courage to talk to her husband about it. Two days earlier, Baldwin was at the girl’s house, pleading with her to get on a plane to a rehab facility in another state. In most cases, Baldwin’s expectation is that the addict gets into treatment immediately.

In Baldwin’s opinions, the treatment options that are so well-publicized, including methadone clinics and Suboxone prescriptions, are short-sighted and ineffective. Those drugs might take away the cravings for opiates, but they don’t get to the root or the problem and address the addict’s behavior and personality.

“You need therapy and analysis, and short detox stays don’t do enough,” he said. “Less than three in 100 who go to rehab for just one month stay sober for a year. The numbers don’t lie.”

Baldwin is frustrated with the lack of options in Upstate New York, and he is lobbying state lawmakers to appropriately fund longer-term rehab centers in the wake of this opiate epidemic. He sees potential in every community. A pizzeria in Auburn, for example, could be the ideal place to employ recovering addicts after they are discharged from rehab. The routine of steady employment is key to staying sober. He wants to lease a vacant school building down the road from him in Cleveland, which he envisions is large enough to house a long-term recovery facility.

“There is push-back from the locals,” he said. “They say they don’t want a bunch of junkies coming here, but I tell them they are already here. Where would you rather have them — in treatment, or burglarizing your homes and businesses?”

Baldwin speaks at area high schools, hoping to discourage youngsters from ever trying opiates or painkillers. For the high school quarterback, for example, problems can start with an over-generous prescription of Vicodin for pain treatment following an injury. The quarterback becomes addicted because with the amount of pills he gets he doesn’t have to manage the dosages and endure a little discomfort between doses. He gets more pills on the black market, and eventually discovers that heroin is cheaper.

And then there’s the story about a Wal-Mart in the Southern Tier that doesn’t have enough part-time employees. “They can’t find enough kids there under 25,” Baldwin said, “because so many are into heroin.”

Greg Hannley, chief executive officer of SOBA and Baldwin’s close friend and sponsor, called the actor’s determination remarkable. “He’s constantly at service. He is someone who really cares, and he always goes where he’s needed.”

Hannley has treated hundreds of Hollywood types. He said most people don’t understand the unique challenges entertainers face in getting sober. “There’s nowhere they can go to hide from it,” he said. “Everywhere they go, there are people who want to get high with a celebrity.”

Hannley accompanied Baldwin on a trip to Syracuse from Toronto. They drove six hours in a blizzard. The teen-ager who traveled with them was not familiar with Baldwin but his mother was a big fan.

“I told the kid, you have a movie star risking his life to get here because your mom is so worried about what is happening to you,” Hannley said. “That was 11 years ago. That kid is sober now and has a good job. He’s married, has a job and a wonderful life.”

When Baldwin gets totally settled into his new life in Cleveland, perhaps in the winter time when there isn’t as much to do outside, he’ll start work on a book about his battle with addiction.

“I want to write about the struggles and how I got where I am, but I don’t like the idea of writing the book for myself,” he said. “It has to be for others. That’s part of the path to sobriety.”

Help with Sobriety

Daniel Baldwin has a monthly talk show on sobriety that is shot in San Antonio, Texas. The show — “SOBA Life” — is available to a national cable audience. You may watch it live at foxsanantonio.com

If you need help with a sobriety issue, you may reach Daniel Baldwin through his email address, baldwinhelp@icloud.com

Getting to Know Your New Neighbor

Age: 57

Hometown: Massapequa, Long Island.

Current Residence: Cleveland, Oswego County. He remodeled a farm house built in 1828.

Family: Fiancé Robin Hemple and daughters Avis and Finley. His mother, Carol, lives in Camillus. His sisters, Beth and Jane, also reside in Central New York. Brothers Alec, William and Stephen, who are also actors, live in different locations but have visited Central New York regularly.

Occupation: Actor, director, producer, writer, drug addiction outreach specialist

Hobbies: Fishing in Oneida Lake, golf, tennis, basketball.

On Dieting:

Baldwin has taken on a new diet called the “Robert Ferguson Challenge.” The meal plan follows a very precise combination of starches and protein. So far, he’s lost 30 pounds in 42 days, and he hasn’t even started the physical training part of the plan yet.

“I’ve had diets before where the science wasn’t there, but the motivation was different,” he explained. “You hear the three dreaded words — veggies, fish and lots of water. But when the reason for losing weight is to be fit for a scene where you’re making love, you’re immediately motivated. I could drop from 250 pounds to 225 pretty quickly.”

On Discovering Central New York:

“Being here, I feel like the theme is Green Acres. We just love discovering the area. It’s exciting to get into a car and drive and not even know what we’re going to see.”