Breaking Down Barriers

Max Smith, retired city of Oneida mayor, reflects on how abolitionists mission has gone from slavery to racism

By Debra J. Groom

There hasn’t been a day in Max Smith’s adult life that he hasn’t been serving his fellow man.

This has occurred from his years working with the developmentally disabled in Madison County and the state ARC to his singing at numerous events such as the Martin Luther King Jr. breakfast in Rome. He was mayor of Oneida and represented part of Oneida on the Madison County Board of Supervisors.

He has worked with Medicaid recipients on their yearly recertifications. Today in retirement, he is helping senior citizens find just the right Medicare supplement plan so they can rest easy in their golden years.

And on top of it all, Smith volunteers hours of his time to tell the story of another Smith — Gerrit Smith of the tiny Madison County hamlet of Peterboro — and his abolitionist work in the 1800s.

Max Smith is descended from slaves on both sides of his family who lived and worked in Peterboro. Max Smith works with the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum on its board and as a docent. He has learned more about Gerrit Smith and the importance of ensuring the abolitionist’s story is known far and wide.

The mission statement for the Hall of Fame and Museum says it all: “The National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum honors antislavery abolitionists, their work to end slavery and the legacy of that struggle, and strives to complete and second an ongoing abolition — the moral conviction to end racism.”

“I can’t talk about it without crying,” Smith said as tears welled in his eyes. “I am humbled and proud to work with them.”

The voice

Smith, whose full given name is Alden Maxwell Smith, is 66 and was born in Canastota. He has lived most of his life in the city of Oneida.

He remembers his childhood as filled with fun with neighborhood kids, whether it was heading over to Otto Behr’s house and playing baseball all day or simply running around outside. The Smiths were a musical family and all the kids in his family played musical instruments.

Smith took piano lessons, “but I was always more interested in baseball,” he said. He regrets quitting piano to this day.

But nothing could hold back his robust baritone voice. He loved to sing and thought he might be another Luciano Pavarotti.

“In the ‘80s, I was the front man for a wedding band,” he said. “I was the cantor at St. Agatha’s (Roman Catholic church in Canastota).”

He later became what he called the Peterboro Troubador, “singing slave songs and spirituals” at African-American events throughout Central New York. It was through these singing engagements that he became involved with the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum.

Abolition today

Strangely enough, Smith didn’t grow up knowing much about Gerrit Smith and anti-slavery work done in Peterboro, which is a short 11.5 miles from Oneida.

He got more deeply involved in the abolitionist movement when he wanted to put together a program merging some of his slave songs with the spoken word presentation to perform at sites throughout Central New York.

He joined forces with former Madison County Court Judge Hugh Humphreys, who had written many plays about the Underground Railroad, the abolitionist movement and its Madison County roots. And through his research, he found some of his own family members were part of the story.

“I was embarrassed by how much I didn’t know,” Smith said.

Through a fundraiser at the Morrisville Library, he and Humphreys were able to put together an African-American music program that was performed at the Earlville Opera House, at elementary schools and other places. The program featured slave songs with history and narrative.

From there, Smith wanted to know more. He became involved with the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum.

It was the organization’s mission statement that really hit Smith hard. He said the mission statement — which talks about the abolitionists struggle to end slavery and today’s work to end racism — means so much to him because he thinks of what Gerrit Smith and the abolitionists of the 1800s did as compared to people working at the hall of fame and museum and those protesting racism today.

“The abolitionists didn’t work for the African-Americans, they worked with the African-Americans to end slavery,” he said. He said the same is true today as many white people work with blacks to end racism.

“About 18 of them take time off and put their effort and dedication into the hall of fame and museum,” Smith said. He said all the work at the museum and the dedication being shown throughout the world to end racism “is the fiber of America that empowers me.”

He thinks about what the abolitionists went through in the 1800s as they fought to end slavery and how that compares to what is happening in the U.S. today.

“I think what happened with the abolitionists is often overlooked and forgotten,” he said. “There was a lot of resentment and hostility toward them. [Famed abolitionist] William Lloyd Garrison was beaten and stoned. Abolitionists were run out of town. They put their lives on the lines.”

Today, similar situations are occurring with white people trying to end racism. Smith said it is “discouraging in some ways” to think people still are fighting about the treatment of African-Americans today, more than 150 years after the end of the Civil War.

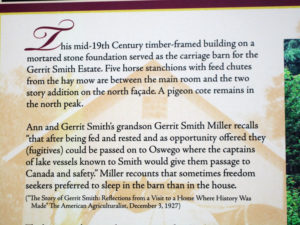

In addition to his work at the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum, Smith has been a focal point in planning the annual Emancipation Celebration in Peterboro, held in August to celebrate the freedom from slavery of so many people who lived in Peterboro and Madison County or traveled through on their way to Oswego and Canada. This year’s event has been canceled.

He also was a key member of the group who put together the Underground Railroad Consortium display and information at the New York State Fair.

Involved in politics

Smith began his time in politics as an Oneida Common Council member. He served from 1992-95, 1998-99 and then again from 2008-2012. In 2012, he was appointed Oneida mayor after the death of Mayor Donald Hudson. He was reelected to a full term in 2013.

Smith caused a bit of a political ruckus when he changed parties from Democrat to Republican during one of his common council runs.

“I found myself increasingly at odds with the Democrat mayor,” he said. “I told the Democrats I cannot be on the ballot with him — this is about personal integrity.”

He said the Democrats told him it would be political suicide to leave and run for his council seat as a Republican. But, they were wrong as he won by an even greater margin.

The mayor at the time was Army Carinci, who served as mayor from 1986-99.

Smith is most proud of an accomplishment during his time as mayor when sidewalks finally were installed on the upper end of Lenox Avenue to Walmart. He said the common council had tried for years to get sidewalks put in that location for the many people who walked to Walmart to shop.

“In our initial efforts, we were told there was no money for the sidewalks,” he said, noting the project was going to cost about $750,000. But when he became mayor, he reached out for help to various county, regional and state officials. Eventually, the state Department of Transportation approved the project.

But Smith also is proud of the legacy he has left for all minorities in the city of Oneida and elsewhere. He said through work with the Madison County Historical Society, he was able to pin down that he was the first African-American ever elected to the Oneida Common Council or as Oneida mayor.

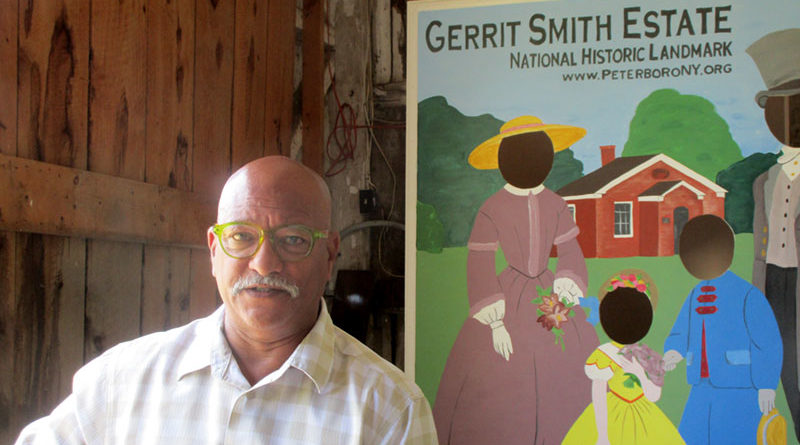

Photo: Max Smith inside the barn at the Gerrit Smith Estate in Peterboro; the estate is part of the National Historic Site that tells the story of abolitionist work during the 1800s. Photo by Debra J. Groom.