The True Sound of Music

Kerner and Merchant Pipe Organ Builders: in the business of making music sound better

By Carol Radin

When we respond to the serenity of a Bach or Brahms chorale or a triumphant Handel chorus, we can marvel at the sense of wonder created by the chords of the pipe organ.

Ben Merchant understands how that sense of wonder happens from inside out—literally.

As president of Kerner and Merchant Pipe Organ Builders, East Syracuse, Merchant heads a company that has been providing maintenance and service for organs in religious institutions, concert halls and colleges all over the Upstate and Central New York areas for more than 40 years.

The company also builds organs and does re-builds and historical restorations.

Among the major rebuilds displayed on its website are the organs in the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Syracuse, the Franciscan Church of the Assumption Church, also in Syracuse, and the First United Presbyterian Church, Troy. They have restored organs for Syracuse University, Hamilton College in Clinton and the Unitarian Universalist Church in Canton, among others.

Merchant, 69, a Schenectady native, is also a musician. He plays the organ and the harpsichord and he sings. After his college years at SUNY-Albany and Syracuse University, where he earned his degree in music history, he started out in organ maintenance by tuning organs.

He apprenticed with Leonard Carlson, a master organ builder, and Walter Burr, a harpsichord builder. While at SU, Merchant met Rob Kerner. Together they founded Kerner and Merchant in 1977.

While Kerner is now retired, Merchant continues in the business with three co-owners, A. Hawley Arnold, 55, Christopher Fuller, 31 and Stefan Merchant, 29, who is Ben Merchant’s son. They succeed as a team by collaborating across two generations, learning from each other and complementing each others’ skills sets.

Arnold, now the corporate secretary, has been rolling up his sleeves with Kerner and Merchant since 1980.

“I am the old quote-unquote gray-haired expert,” he said.

In his other life, he is also the choir director and organist for Jordan United Methodist Church in Jordan, where he’s been for 42 years and counting. Arnold started playing the organ in junior high school. However, building an organ? No interest, he said.

Then, he met Merchant when his church employed the services of Kerner and Merchant. It was, Arnold recalled, “A whole other level of the pipe organ.” Soon after that, he started out with the company part-time, usually holding the keys for the tuner, since he has what’s known as a good ear.

“I would just go around seeing bigger instruments than I’d ever seen,” he said.

He got hooked and gradually just “learned more and more on the job.” With degrees in music history and music education, he can also relate on an academic level to instructional principles and to professional development. He has done some demonstrations, attends conventions and enjoys collegiality with the teaching staffs at the colleges where the company maintains organs. Ever the student, he approaches his work with an open mind. “I’m still growing into it!” he said. That’s a modest estimation from someone who is actually a mentor for Fuller and Stefan Merchant, who look to Arnold for historical knowledge, that good ear for tuning and general all-around support.

Fuller himself might say he’s still growing into it, though he has done so with Arnold by his side.

“I knew absolutely nothing about pipe organs!” Fuller admitted. His instruments are the trumpet, piano and guitar. His musical tastes are more inclined to the rock band Cold Play and the “honest music” of country singer Colton Wall. Growing up in Jordan, however, Fuller got to know Arnold through church and started helping out at the Kerner and Merchant workshop during summers while in high school. Like Arnold, he got taken in. “There’s a lot of woodworking and construction. It really intrigued me. I had not had access to this different level of tools,” he said.

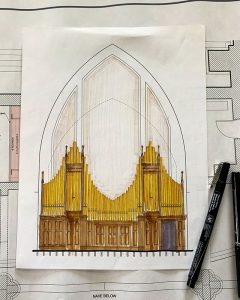

In college, he studied architecture.

“A pipe organ is similar to residential architecture. It has structure, design, building a façade, ergonomic design, electrical components. It is micro-skill building,” he said.

To master the specialized hands-on skills required for this job, though, Fuller looks to Arnold.

“We wouldn’t be in business if we couldn’t rely on that institutional knowledge,” said Fuller. As the company’s vice president, Fuller looks forward to all opportunities to more fully engage in new ideas and to help the company’s strategy and structure continue to evolve.

For Stefan Merchant, 29, joining his father’s company full-time as a managing partner was not a stretch. His is a musical family. Ben Merchant has instilled in Stefan an appreciation for the organ, religious music, and church architecture. Stefan’s mother, Julie Pretzat, is currently director of the Syracuse Vocal Ensemble, in which Ben Merchant sings. Stefan himself sings in a pop band. He likes to recall, that as a child, he would be allowed after church to climb the ladder up to the organ, where the organist “would let me operate the stops.” (the controls that operate sets of pipes).

“It was my version of the jungle gym!” he said.

What started out as play gradually seeped in and Stefan started working in the business during high school and college breaks. He left the area for the University of Colorado, where he earned a degree in arts and geography. Self-evaluation, the appeal of the work, and years of guidance from his father led him to seriously pursue organ-building and maintenance.

While the piano is his instrument rather than the organ and his listening preferences tend toward hard rock, like the rock trio Chevelle or the electrical music of Kiko, he does love the physical process of organ-building.

He breaks into a smile as he describes getting inside the organ chamber itself, working on the reservoirs (storage boxes for organ wind and for regulating wind pressure), restringing, and all the other intricate processes of “assessing and putting back together.” Though Stefan found that he knew more than he first realized when he came into the business, he discovered so much more on the job by working with his father and with Arnold and Fuller.

“We each come at it from a different perspective,” Stefan said. “My father is the jack-of-all-trades. He’s taught me about different types of pipes, families of sound, chest designs, how to diagnose problems,” among other aspects of building and restoration. From Arnold, Stefan learned much more about wiring. He also counts on Arnold’s command of music history.

“If there’s something I don’t see very often, he’s the one I go to,” he said.

And from Fuller, who is regarded by all his colleagues as a great cabinet-maker, Stefan acquired essential woodworking skills.

The on-the-job learning is just that, more an intergenerational sharing of expertise, rather than a formal classroom experience. What makes it work is what the four share in common, a love of music and a talent for creating with their hands. Even in his spare time, Ben Merchant’s pastimes are tinkering with cars and restoring antiques. He is now building a harpsichord. For organ-building itself, fine cabinet-making is a core competence. That fine woodworking must be combined with wiring and fitting strings, pins, bridges and many other intricate components of manual construction that the average music listener has no idea of.

Nor do most listeners realize what goes into maintaining an organ season by season. Generally organists are advised to have organs checked twice a year. The company routinely maintains 150 organs. At this time of year, they will service 20–30 organs per week, with assistance from one additional full-time employee and as many as seven part-timers.

“Everyone wants their organ to sound good for Christmas,” Merchant said.

All sorts of questions and extra repairs will pop up and the company has been known to save the day.

“One time, I got an emergency call from a frantic organist. ‘The organ was ‘badly out of tune. Could I come and help?’ I rushed to the church on Christmas Eve and climbed up into the organ and found a Hacky Sack on the organ chest. Evidently some teens were playing in the church and the ball had gotten kicked up into the pipes and knocked several crucial pipes out of tune!”

These are what Merchant typically calls “UFOs: unwanted flying objects, like insects, birds, bees, moths, bats, dust and dirt.”

As the veterans, Merchant and Arnold have seen the business change radically over four decades. Time and again, they have lived Arnold’s mantra, “You never stop learning.” Design and specifications for re-building are now computer-aided. Previously, organs operated with sets of electro-mechanical switches. Today, those sets of switches have been replaced with microprocessors. Computer cables have been replaced by fiber optics. How to deal with the learning curve? “We taught ourselves,” Ben Merchant explained, describing their calls to manufacturers, ordering manuals, and poring over them. While it can be head-scratching at times, Ben Merchant keeps what’s most important foremost in his mind, “What makes pipe organs good are the pipes and the acoustics and THAT hasn’t changed,” he said.

The business itself is adjusting to the reduction of organs in the area, as some church and temple buildings close.

Expanding their region to a three-hour radius was part of that adjustment. As vice president, Fuller is seeking to redefine the company’s strategy to deal with the diminishing role of the organ in religious and cultural life. Getting more creative is not out of the question for him.

“We’re thinking of an organ in its traditional aspect, but what else can it be? Can it be something way more interactive? Can that be done?” he said.

He contemplates the possibilities of making the instrument more visible, more accessible in more venues and more interdisciplinary.

“How awesome would it be to open up these things?” Fuller said.

Conversations with religious groups, who can no longer keep their buildings, while becoming more frequent, are not just a business transaction for Ben Merchant, who values organ music as an important dimension in his own life.

“I hate it when there’s a beautiful organ in a beautiful sanctuary, but they can’t afford to maintain their sanctuary!” he said.

Fuller too admits developing an emotional attachment to this instrument that takes on a life far beyond the physical materials. Rebuilding an instrument can take a year, so that’s a year of devoted commitment to one project. Most were originally built more than a century ago.

“You’re second in touching this,” Chris said. “There’s a part downstairs we’re restoring now. A person one hundred years ago signed his name inside and we wouldn’t have found that until we opened it up!”

So beyond the measurements and the materials, Chris and his colleagues touch a part of history and sustain continuity and reverence for something really beyond articulation. And when they complete their work, we have music! Quite wondrous after all.